Mike Tyson's tattoos

The American former boxer Mike Tyson has four tattoos that have received significant attention. Three—portraits of tennis player Arthur Ashe, Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara, and Chinese communist leader Mao Zedong—are prison tattoos he received in the early 1990s, reflecting Tyson's respect for the three men. The fourth, a face tattoo influenced by the Māori style tā moko, was designed and inked by S. Victor Whitmill in 2003. Tyson associates it with the Māori being warriors and has called it his "warrior tattoo", a name that has also been used in the news media.

Tyson's face tattoo quickly proved iconic and has become strongly associated with him. Its Māori influence has been controversial, spurring claims of cultural appropriation. In 2011, Whitmill filed a copyright suit aganst Warner Bros. for using the design on the character Stu Price in The Hangover Part II. After initial comments by Judge Catherine D. Perry denying an injunction but affirming that tattoos are copyrightable (a matter which has never been fully resolved in the United States), Whitmill and Warner Bros. settled for undisclosed terms, without disruption to the release of the film. The legal action renewed claims of cultural appropriation but also saw some Māori tā moko artists defend Whitmill. Legal scholars have highlighted how the case juxtaposes Maōri and Anglo-American attitudes on ownership of images.

Portraits of Ashe, Guevara, and Mao[edit]

From 1992 to 1995, while in prison for the rape of Desiree Washington, Tyson read a large number of books, including works by Chinese communist leader Mao Zedong.[1] Spike Lee sent Tyson a copy of tennis player Arthur Ashe's deathbed memoir, Days of Grace. Tyson was moved by the book and respected Ashe's ability to be nonconfrontational[2] and admired his political views and his success as a Black athlete in a white-dominated world.[3] Tyson got prison tattoos of both men on his biceps: A portrait of Mao, captioned with "Mao" in all-caps, on the left; a portrait of Ashe beneath the words "Days of Grace" on the right.[4] Gerald Early views the Mao and Ashe tattoos as together "symboliz[ing] both [Tyson's] newfound self-control and his revision of black cool", with Mao representing strength and authority.[5]

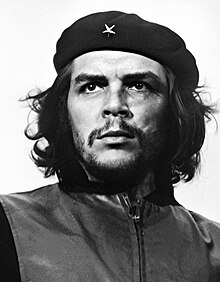

Tyson chose tattoos of Mao and Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara to reflect his anger at society and the government while in prison.[6] The Guevara tattoo, located on the left side of Tyson's abdomen, is derived from Alberto Korda's iconic Guerrillero Heroico photograph.[7] In Tyson, Tyson brags that the tattoo predated the widespread commodification of Guevara's image.[6] Tyson maintained positive views of both revolutionaries after leaving prison: In 1999 he described Guevara as "Someone who had so much but sacrificed it all for the benefit of other people."[8] In 2006 he visited the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall and said that he "felt really insignificant" in the presence of Mao's body.[9]

Face tattoo[edit]

| The tattoo process | |

|---|---|

Tyson got his face tattoo from artist S. Victor Whitmill[a] of Las Vegas, Nevada, shortly before Tyson's 2003 fight with Clifford Etienne, which would be his 50th and last victory.[11] Tyson had originally wanted hearts, but, according to Tyson, Whitmill refused and worked for a few days on a new design.[12] Whitmill proposed a tribal design[13] inspired by tā moko,[b] a Māori tattoo style reserved for those of high status.[14] The design is not based on any specific moko.[15] Tyson saw the tattoo as representing the Māori, whom he described as a "warrior tribe", and approved of the design,[16] which consists of monochrome spiral shapes above and below his left eye.[17] According to Tyson, it was his idea to use two curved figures rather than one.[18]

The tattoo drew significant attention before the fight. Tyson took time off of training to get it, which trainer Jeff Fenech would later say was a contributing factor to the fight being rescheduled by a week.[19] Experts including dermatologist Robert A. Weiss expressed concerns about Tyson boxing while the tattoo healed; Etienne said that he would not go after the tattoo.[20] (Tyson ultimately knocked out Etienne in under a minute.[2]) The work—which Tyson[21] and others[22] have referred to as his "warrior tattoo"—was also met with criticism from the outset by Māori activists who saw it as cultural appropriation.[17]

Rachael A. Carmen et al. in the Review of General Psychology posit that Tyson's face tattoo may be an example of "body ornamentation as a form of intimidation".[23] Charlie Connell and Edmund Sullivan in Inked describe it as having become "instantly iconic".[2] Its prominence has increased over time, aided by Tyson and the 2009 comedy The Hangover, in which Tyson appears as a fictionalized version of himself.[24] The tattoo has become strongly associated with Tyson and has made his persona more distinctive.[23]

The Hangover Part II copyright suit[edit]

When Tyson got the face tattoo, he agreed in writing that all drawings, artwork, and photographs of it belonged to Whitmill. In The Hangover's 2011 sequel, The Hangover Part II, the character Stu Price gets a face tattoo almost identical to Tyson's. After seeing a poster depicting the tattooed Stu, Whitmill sued Warner Bros. under the Copyright Act of 1976 on April 28, 2011, seeking to enjoin them from using the tattoo in the movie or its promotional materials.[25] Describing the face tattoo as "one of the most distinctive tattoos in the nation",[26] Whitmill did not challenge "Tyson's right to use or control his identity"[27] but challenged Warner Bros.' use of the design itself, without having asked his permission or given him credit.[25] Warner Bros. acknowledged that the tattoos were similar but denied that theirs was a copy, and furthermore argued that "tattoos on the skin are not copyrightable".[28] The question of a tattoo's copyrightability had never been determined by the Supreme Court of the United States.[29] Warner Bros. also said that, by allowing them to use his likeness and not objecting to the plot device in The Hangover Part II, Tyson had given them an implied license.[30]

On May 24, 2011, Judge Catherine D. Perry denied Whitmill's request to enjoin the film's release, citing a potential $100 million in damages to Warner Bros. and disruption to related businesses. However, she found that Whitmill had "a strong likelihood of success" on his copyright claim and characterized most of Warner Bros.' arguments as "just silly", saying "Of course tattoos can be copyrighted. I don't think there is any reasonable dispute about that." She also described the tattoo used in the movie as "an exact copy" rather than a parody.[30] On June 6, Warner Bros. told the court that, in the event the dispute was not resolved, it would alter the appearance of the tattoo in the movie's home release;[31] on June 20 it announced a settlement with Whitmill under undisclosed terms.[32]

Many Māori took issue with Whitmill suing for copyright infringement when the work was, in their view, appropriative of moko. Ngahuia Te Awekotuku, an expert on Māori tattoos, told The New Zealand Herald that "It is astounding that a Pākehā tattooist who inscribes an African American's flesh with what he considers to be a Māori design has the gall to claim ... that design as his intellectual property"[33] and accused Whitman of having "never consulted with Maōri" and having "stole[n] the design".[34] Some tā moko artists differed, seeing it not as appropriative of moko but rather a hybrid of several tattoo styles; Rangi Kipa saw no Māori elements at all.[35] The perspective of those like Te Awekotuku highlights the conflict between Māori conception of tā moko—which reflect a person's genealogy—as collective property and the Anglo-American view of copyright as belonging to a single person.[36] While Warner Bros. initially said they would investigate whether the tattoo was a derivative of any Māori works, there was no further discussion of the matter prior to the case settling.[15]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Hoffer 1998, p. 36: "Of his prison belongings, the only things that returned home to Ohio with him were more than 20 banana boxes full of books—Voltaire, Maya Angelou, Machiavelli, Alexandre Dumas." Cashmore 2005, pp. 91, 242: "a newfound appetite for reading literature. Diverse literature too: from the works of Tolstoy to that of Mao Zedong, the latter the inspiration for a new tattoo."

- ^ a b c Connell & Sullivan 2022.

- ^ Early 1996, p. 59. Early says that Ashe was, according to Tyson, "not a man [Tyson] would have liked personally". In Connell & Sullivan 2022, Tyson describes a respect and kinship felt for Ashe.

- ^ Hoffer 1998, pp. 36, 266; Roche 2020.

- ^ Early 1996, p. 59.

- ^ a b Toback 2008, 58:51.

- ^ Cambre 2012, p. 84.

- ^ Williams 1999.

- ^ Chicago Tribune 2006.

- ^ Reuters 2003, 2:37; Toback 2008, 59:32; Bensinger 2016, 0:22.

- ^ Toback 2008; Inked 2020; Connell & Sullivan 2022.

- ^ Bensinger 2016; Connell & Sullivan 2022.

- ^ Zhitny, Iftekhar & Sombilon 2021, p. 79.

- ^ Hadley 2019, p. 401. "In Māori culture, facial moko is a privilege reserved for respected cultural insiders, and it represents and embodies the wearer's sacred genealogy and social status."

- ^ a b Hadley 2019, p. 402.

- ^ Toback 2008, 59:46; Tan 2013, p. 64.

- ^ a b Hadley 2019, p. 401.

- ^ Bensinger 2016, 0:52.

- ^ AP 2003. Hamdani 2020, quoting Fenech: "'We sat down and spoke and he didn’t really want to fight and he wasn’t prepared to and that was one of the reasons he got the tattoo. ...'"

- ^ Glier 2003a; Glier 2003b.

- ^ AP 2003.

- ^ Anderson 2003; Rea 2009; Choi 2012; Hadley 2019, pp. 401, 407.

- ^ a b Carmen, Guitar & Dillon 2012, p. 141.

- ^ Tan 2013, p. 64.

- ^ a b Cummings 2013, p. 280; Grassi 2016, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Cummings 2013, p. 280, quoting Whitmill complaint 2011, p. 1.

- ^ Whitmill complaint 2011, p. 1.

- ^ Cummings 2013, p. 281, quoting Whitmill answer 2011, p. 8.

- ^ Cummings 2013, p. 281.

- ^ a b McNary 2011.

- ^ Labreque 2011, citing Whitmill memo in opposition 2011

- ^ Belloni 2011.

- ^ Tan 2013, p. 66, quoting NZ Herald 2011. Ellipses original to Herald.

- ^ NZ Herald 2011.

- ^ Hadley 2019, pp. 402–403.

- ^ Tan 2013, pp. 66–67; Hadley 2019, p. 403.

Sources[edit]

Book and journal sources

- Cambre, Carolina (October 1, 2012). "The Efficacy Of The Virtual: From Che As Sign To Che As Agent". Public Journal of Semiotics. 4 (1): 83–107. doi:10.37693/pjos.2012.4.8839.

- Carmen, Rachael A.; Guitar, Amanda E.; Dillon, Haley M. (June 2012). "Ultimate Answers to Proximate Questions: The Evolutionary Motivations behind Tattoos and Body Piercings in Popular Culture". Review of General Psychology. 16 (2): 134–143. doi:10.1037/a0027908. S2CID 8078573.

- Cashmore, Ellis (2005). Tyson: Nurture of the Beast. Cambridge, England: Polity. ISBN 9780745630700. OL 3434892M.

- Cummings, David M. (2013). "Creative Expression and the Human Canvas: An Examination of Tattoos as a Copyrightable Art Form" (PDF). University of Illinois Law Review. 2013: 279–318. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- Early, Gerald (1996). "Mike's Brilliant Career". Transition. Indiana University Press (71): 46–59. doi:10.2307/2935271. JSTOR 2935271.

- Grassi, Brayndi (January 1, 2016). "Copyrighting Tattoos: Artist vs. Client in the Battle of the (Waiver) Forms". Mitchell Hamline Law Review. 42 (1): 43–69. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- Hadley, Marie (April 17, 2019). "Mike Tyson Tattoo". In Op den Kamp, Claudy; Hunter, Dan (eds.). A History of Intellectual Property in 50 Objects. Cambridge University Press. pp. 400–407. doi:10.1017/9781108325806.050. ISBN 9781108325806. S2CID 198060965. SSRN 3654612.

.

. - Hoffer, Richard (1998). A Savage Business: The Comeback and Comedown of Mike Tyson. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780684809083. OL 689533M.

- Tan, Leon (May 2013). "Intellectual Property Law and the Globalization of Indigenous Cultural Expressions: Māori Tattoo and the Whitmill versus Warner Bros. Case". Theory, Culture & Society. 30 (3): 61–81. doi:10.1177/0263276412474328. S2CID 144418522.

- Zhitny, Vladislav Pavlovich; Iftekhar, Noama; Sombilon, Elizabeth Viernes (2021). "History, Folklore, and Current Significance of Facial Tattooing". Dermatology. 237 (1): 79–80. doi:10.1159/000505647. PMID 31972563. S2CID 210883478.

News coverage

- Anderson, Dave (February 24, 2003). "Translating Tyson Raises More Questions". Sports of The Times. The New York Times. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- "Tyson displays old power in first-round KO of Etienne". Boxing. ESPN. Associated Press. February 23, 2003 [2003-02-22]. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- Belloni, Matthew (June 21, 2011). "Hangover tattoo lawsuit settled". Reuters. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- "Chairman Mao humbles Tyson". Chicago Tribune. April 4, 2006. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- Choi, Christy (September 13, 2012). "Mike Tyson tells his tales of redemption in Hong Kong". South China Morning Post. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- Glier, Ray (February 20, 2003a). "Tattooed Tyson At Center Of Storm". Boxing. The New York Times. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- Glier, Ray (February 22, 2003b). "With Luster Faded, Tyson Places Career On the Line Tonight". Boxing. The New York Times. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- Hamdani, Adam (April 10, 2020). "The controversial reason behind Mike Tyson's face tattoo". The Independent. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- "Mike Tyson's planning to tattoo it all". Inked. April 20, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2023.

- Labreque, Jeff (June 10, 2011). "Warner Bros. plans to alter Hangover tattoo for video". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved March 2, 2023 – via CNN.

- McNary, Dave (May 24, 2011). "Judge OKs release of Hangover 2". Variety. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- "Tyson's moko draws fire from Māori". The New Zealand Herald. May 24, 2011. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- Roche, Calum (November 29, 2020). "Mike Tyson Mao tattoo: what does it mean and why did he get it?". Diario AS. Retrieved February 26, 2023.

- Williams, Richard (January 13, 1999). "Tyson does Las Vegas". The Independent. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

Interviews and profiles

- Bensinger, Graham (March 3, 2016). "Mike Tyson: The real story behind my tattoo". In Depth with Graham Bensinger (Video interview). Retrieved February 28, 2023 – via YouTube.

- Connell, Charlie; Sullivan, Edmund (November 15, 2022). "The Tao of Tyson". Inked (Profile). Photos by Mark Clennon. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- "USA: Boxing—Mike Tyson and Clifford Etienne weigh in for heavyweight fight" (Interview and raw footage). Reuters. February 25, 2003. Retrieved February 28, 2023 – via Screenocean.

- Toback, James (director) (2008). Tyson (Documentary film). Sony Classics.

Other sources

- Rea, Steven (May 7, 2009). "Engrossing portrait, not entirely credible". The Philadelphia Inquirer (Film review).

- S. Victor Whitmill v. Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc., No. 4:11-CV-752 (E.D. Mo.).

- "Complaint Verified for Injunctive and Other Relief". April 28, 2011. Retrieved March 1, 2023 – via Justia.

- "Verified Answer to Complaint". May 20, 2011. Retrieved March 1, 2023 – via Justia.

- "Warner Bros.' Memorandum in Opposition to Plaintiff's Proposed Scheduling Plan". May 20, 2011. Retrieved March 2, 2023 – via Justia.

.jpg/220px-Cartherine_D._Perry_1_(cropped).jpg)